Strategy for the attack on the Moncada Garrison: an interview with the Swedish TV

Autor:

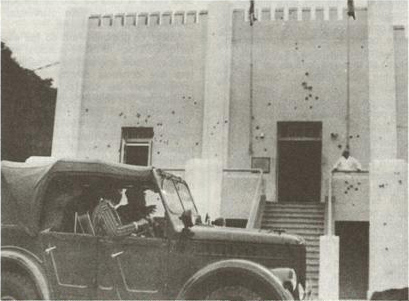

CUBA INTERNACIONAL magazine printed, for the first time ever, a wide selection of interviews in which Fidel Castro discussed his political evolution and made interesting statements on the historic actions that were led and promoted by him. The Cuban President toured the eastern Cuba region that more than twenty years ago had witnessed the events that gave rise to the Revolution. At the old Moncada Garrison, Las Coloradas beach and the mountain sections of Pico Turquino and La Plata, Fidel spoke extensively with his accompanying Swedish reporters who filmed their dialogue for their TV service. The highlights of this interview are carried by this edition that ushers in the year that marks the 25th anniversary of the attack on the Moncada Garrison.

I.BACKGROUNDS

I.BACKGROUNDS

THE MIND OF A HUMAN BEING CAN RISE ABOVE HIS CLASS ORIGIN

Reporter: Comandante, yesterday, at Granja Siboney estate, you discussed your ideological and political evolution while you were at the university. I have a question that focuses on the period before that; i.e., can you describe your ideological evolution from the education you first received at home with your family? At your speech before Cuban intellectuals you used a very strong and vivid image and indicated that the bourgeois education was like a rock mill that can nearly grind one’s mind for ever. That description struck me; that’s why I wanted to ask you.

Commander-in-Chief Fidel Castro: My backgrounds… I was born to a landowning family; however, my parents didn’t have a landowner’s mind. What does that mean? My father was a Spanish peasant from a very humble family. He came to Cuba as a Spanish immigrant at the turn of the century.

He began to work in difficult conditions. He was an enterprising man who excelled himself. He became a sort of labor leader in the early years of the century. In the process, he made money and purchased land. In other words, he was a successful businessman who eventually owned large tracks of land - if my memory doesn’t deceive me, around 1 000 hectares. That was not very hard to achieve in the early years of the Cuban republic. Afterwards, he leased other pieces of land. By the time I was born, my family could be defined as a landowner home.

My mother, by contrast, was a very poor and humble peasant. This is why my family didn’t have any tradition of what can be regarded as oligarchy. Notwithstanding, our social position at that time was one of a family that enjoyed relatively abundant economic resources. It owned land and enjoyed all the comfort and privileges of a Cuban landowning family.

Photo caption: Fidel as a child

In regards my early education… I learned how to read and write at my local public school in the countryside. When I was 5 or 6, I was sent to Santiago de Cuba. I had a hard time there, and I even went hungry in spite of the fact that my parents were paying the lodge where I was staying in Santiago de Cuba. But for some circumstances, a relative large number of kids were housed in that lodge, and we had a hard time during that period.

Reporter: In other words, yours was not a privileged childhood really.

Fidel: When I was at home, it was. When I was sent to Santiago, it wasn’t. I went hungry, I was virtually barefoot. I had to mend my own shoes every time they broke.

Reporter: That explains a lot of things.

Fidel: I found myself in that situation for a little bit more than one year. During that period, one can say that I experienced what poverty was like.

Did that situation influence me? I really can’t tell for sure. Later, I was sent to a Santiago de Cuba private school that was run by a religious order; La Salle Brothers. I completed five grades there. Afterwards, I was sent to a Jesuit school. I completed my education, from elementary to high school, in schools of this nature. These schools were for relatively well-to-do families.

Now, certain factors helped me develop a rebel spirit. I first rebelled against the unfair conditions at the family lodge where I was staying when I was five. At the schools were I was enrolled, I also felt a rebellious drive against certain acts of injustice committed there.

On three occasions during my childhood, I felt things were unfair, hence my drive to rebel. These factors may have helped shape my relatively rebellious character. That rebel spirit may have also been expressed later on in my life.

As a boy, my social interactions during the school break were with the very poor children who lived in the vicinity of my family home.

Reporter: Comandante, can you elaborate this point further?

Fidel: In spite of the financial position of my family, I always socialized with the children of the most humble families who lived around my house in the countryside where I was born. My family didn’t have an aristocratic tradition. As a child and teenager, on more than one occasion, I took a position to reject and rebel against things that I viewed as unfair.

While we received the sort of education imparted by private schools, certain principles of righteousness governed our upbringing.

Elements of my character and spirit may have been shaped during that period of my life; however, I didn’t have any political awareness. The political awareness that helped me understand life, the world, society and history came to me as university student. In particular, I acquired this awareness when I began to read Marxist literature, a great influence on me, which helped me understand matters that I would have never comprehend otherwise.

I gained my political awareness through studies, analyses and observation; rather than by class origin. I don’t think that the class origin is a determining factor; instead, I believe that the mind of a human being can rise above his class origin.

II. MONCADA GARRISON STORMED

FROM THE GARRISON TO THE MOUNTAINS

This estate was chosen because we needed a place to concentrate our forces prior to our attack on the Moncada Garrison. We explored several options and found this house with a small plot of land, which was up for lease. After our review of all the factors involved, we decided to use this house located a few kilometers from the barracks through a straightforward road.

We rented the house, but we needed some pretext to disguise our goal. We came up with a plan to simulate a poultry farm. This is why you see these chicken facilities that in fact were to be used to hide our cars. A few months before we moved in, additional facilities were set up under the pretext of a poultry farm.

Reporter: I understand that his estate was near a house held by one of Batista’s military officers. This element may have helped dissipate any suspicion.

Fidel: Possibly. But that was not the main factor. The main factor was its secluded location off a road that led directly to the vicinity of the barracks. It was one of the very few available sites. Finding a house was not easy.

That house was first used to store our weapons, and later to concentrate our forces. We had to do all this in clandestine conditions. Every measure had to be taken. In fact, we had a neighbor, a peasant who lived across from our house. We made friends with him, and he never suspected that our house had a revolutionary purpose. A member of our movement lived in Santiago de Cuba. He was our only member from that city. We had refused to recruit people from Santiago in order to minimize the risk of indiscretion. This is why we had only one member in Santiago; i.e., the individual who helped us rent the house. Later, one of the movement’s leaders moved in and settled in Santiago de Cuba. For several weeks we transported weapons for storage in this house.

Reporter: The attackers never knew the ultimate objective until the last minute, did they?

Fidel: They didn’t. The movement’s leadership did; in other words, only the three comrades who acted as sort of executive committee of our movement knew. Our comrade from Santiago de Cuba had an idea of our target. He had been given instructions to monitor and explore around the garrison.

Reporter: The cars that eventually drove the attackers to the garrison departed from this house. The weapons were stored here. July 26th was a Sunday, and the attackers gathered here from Saturday night.

Reported: Was the drive more or less the same?

Fidel: It is a several kilometers drive. I can’t remember how far. This road leads to an avenue that skirts the garrison. Tactically, that was the right place for our operation. We could cover our objective with the pretext of a poultry farm business at this house. In fact, everyone believed the story of the poultry farm, or at least our few neighbors across our house had that understanding. The peasant who used to live across our house is still around.

There were a few mango trees… I don’t know if any other trees were planted later. In general, that was the atmosphere around the house.

Reporter: No training operation was conducted here, was it? Only force concentration…

Fidel: It was too risky to train here. We trained in Havana. We used this place to store our weapons, and only one individual from Santiago de Cuba knew about this house. While Santiago de Cuba was home to highly rebellious and revolutionary people, in order to keep our plans confidential, we didn’t recruit anyone from Santiago de Cuba for our attack.

Reporter: In spite of it all, an admirable feature of this movement, as currently reflected in history, was its ability to maintain its wide and clandestine structure under the existing repressive regime.

Fidel: It was in fact very difficult. At that time, the revolutionaries didn’t have an organization or any military experience.

Reporter: By the July 26th Movement did…

Fidel: During that period, a lot of people were trying to set up organizations. As compared to other organizations, our group, in my opinion, recruited the largest number of members. Ours was a very discreet group, not only for the quality of its members, but also for our structure. We had a cell structure. There was not contact among these cells. Our leadership was made up of highly dependable individuals who observed rules of secrecy. In those years, a lot of revolutionaries were very talkative and committed indiscretions. The information about any action that was to be conducted against Batista immediately became public.

Reporter: The weapons imported by the Carlos Prio’s(2) followers and other activities…

Fidel: You are right. Prio’s followers had money, but we didn’t. They had weapons, but we didn’t. Therefore, we had to be more careful. They would make propaganda with their weapons. It could be said that they made politics with their weapons.

Reporter: Weren’t you able to obtain those weapons?

Fidel: We tried to get some. We had infiltrated their organization. We had 360 members infiltrated in their organization. Our purpose was to seize their weapons. Apparently, our plan was too ambitious. At some point, they grew rather suspicious about those guys.

Reporter: But the weapons found by the Batista police during the period were owned by…

Fidel: Them, members of the previous administration. They had a lot of money stolen during their term of office.

Reporter: But some these weapons had been planted by the police in parcels…

Fidel: I don’t think so. The leaders of the political parties and the administration that had been toppled by Batista had a lot of money. They purchased weapons that they managed to smuggle into the country using ingenious procedures. They didn’t have supporters or members; they had money and weapons, but not men. And they were striving to recruit grassroots people. During the same period, we were infiltrating their ranks in order to seize their weapons.

Reporter: But by that time your movement already had many members…

Fidel: We managed to train more than 1 000 men. At that time we were around 1 200 men.

Reporter: But beyond those trained troops, was your organization widespread?

Fidel: It wasn’t so widespread, even if its base was the opposition and hate of the Batista regime. However, its organized and trained members reached around 1 200 members. The opposition of the Batista administration was wide. Many in our ranks, including some of the participants in the Moncada attack, came from the Orthodox Party(3). They were individuals from humble homes. In other words, our organization had nothing to do with those political parties. I selected mostly people who had a humble background. Our people were chosen from the humble sectors of society, people who opposed Batista.

Reporter: However, I understand that many members of your movement had come from the Orthodox Party.

Fidel: They had come from the Orthodox Party: a popular and rather heterogeneous organization. The membership of the Orthodox Party included mostly humble people: workers, peasants and petty bourgeois. By that time, the leadership of that party was controlled by the ruling classes.

Photo caption: In one of his many clashes with the repressive forces, student Fidel confronts the chief of police.

Reporter: Were you a member of the youth league of that party?

Fidel: There was a combative youth league. However, the official party leaders had already compromised their position – not their class position, but they were adapting to the system, so to say. I organized the youth league of that party… separately from official leadership. I worked from the grassroots, mostly with young individuals of humble backgrounds. Our organization had no official leaders of that party. Ours was a political and ideological work…

Fidel: Indeed, we deployed a political and ideological work.

Reporter: By that time, no reference was being made to socialist ideas, right?

Fidel: There was no talk of socialism by that time yet. In that period, the people’s number one objective was to overthrow Batista. However, the social background of the people we had recruited propitiated political indoctrination.

At least the tiny group involved in the organization of our movement consisted of individuals with quite advanced ideas. We used to impart Marxism training courses. And the members of our leadership, all of us, studied Marxism throughout that period. It can be argued that by this time, the main leaders of our movement were already Marxists.

WITHIN A MARXIST CONCEPTION

Reporter: After Chivás died or committed suicide, the differences between his party leadership and the youth league became sharper…

Fidel: I can tell you this: Chivás was a charismatic leader who carried a lot of public support; however, his platform was not one of deep social reforms. In that period, his agenda was limited to some nationalist measures in the face of the Yankee monopolies; mostly measures against administrative corruption and theft. His was a constitutionalist platform and he was fighting for public decency. Chivas’ program was far from being socialist.

At that time, such a platform responded to the expectations of the petty bourgeoisie that already had contradictions with imperialism, for it resented the overexploitation by the monopolies operating in Cuba. Its main banner was the fight against public corruption, theft and embezzlement. However, a left had emerged within the party ranks. We were the left within that party. We weren’t many, but most of us came from the university where we had been exposed to socialist ideas, Marxism-Leninism, and where we acquired a much more advanced political awareness.

By the time Chivas died, he was survived by a massive party without direction. Its leadership was reform-minded. Within those ranks, some of us had much more advanced ideas. In a nutshell: by the end of my university studies, I had a Marxist conception of politics. During my time at the university, my exposure to Marxist ideas helped forge my revolutionary awareness. Ever since, every political strategy I designed was within a Marxist conception.

By the time a coup was staged on March 10, 1952, I already had a Marxist formation. However, we found ourselves in a country stricken by a coup d’état, where the broadest based party was being ill-managed and lacked direction. Before this March 10 coup, I already had concrete, practical and revolutionary ideas.

Reporter: How about the Peoples’ Socialist Party (“PSP” for Spanish)? Did it have any designed strategy?

Fidel: The Socialist Party was relatively small. By Latin American standards, it was large, but it was quite isolated. In that period, the onslaught of McCarthyism and anticommunism had managed to block the Communist Party. I was not a member of the Communist Party because of my education and class origin. It was at the university where I gained a revolutionary awareness. However, I was already a member of a party that was not Marxist-oriented, but populist. Notwithstanding, I felt that this party had great political strength and massive support. Hence, even from before the March 10 coup, I designed a strategy to carry these masses to a revolutionary position. I clearly understood that the revolution must be executed by seizing power first, and that the power must be seized through revolutionary methods. Prior to the March 10 coup, I already had that conviction.

Of course, the strategy I was personally developing before the March 10 coup was consistent with those circumstances. It was a political and parliamentary era. And I was already within that trend. I conceived my initial ideas of a revolution from parliament, not with the intent to make a revolution through parliament. I was planning to use parliament to propose a revolutionary program.

Reporter: Was that the reason why you ran for a seat?

Fidel: I was actually planning to use parliament to propose a revolutionary program, mobilize the masses around it and move to a revolutionary takeover. Since those times, since before March 10, 1952, I wasn’t thinking of relying on the conventional or constitutional roads to power.

Photo caption: With Abel Santamaria and other courageous young men who participated in the historic attack on the Moncada Garrison

When the coup was staged on March 10th, it became necessary to change our strategy. The constitutional avenues could not be utilized.

Reporter: The coup was not meant to prevent a revolution, but rather avoid a takeover by reformists or a more or less progressive party in Cuba, was it?

Fidel: In my view, the coup was meant to prevent the success of a progressive party in Cuba, rather than avoid the triumph of a revolutionary party. That’s a fact. They were trying to halt a progressive movement; however, from a historical perspective, they laid down the conditions to generate a revolutionary movement. In the Cuban conditions, it was possible to promote a revolution, even before March 10.

I had become a communist before March 10, but our people were not communist. The large masses were not responsive to a radical political way of thinking. They were more for a progressive and reformist way of thinking, but no communism.

Reporter: Of course, this situation was being favored by anticommunism and McCarthyism.

Fidel: Significantly. We were an economic and ideological colony of the United States. I became aware of that while I was studying at the university.

WEAPONS ON PURCHASED ON CREDIT

Reporter: Comandante, was this the place where you got in the cars and drove away?

Fidel: Over there is a pit where we hid our weapons. We had acquired our weapons at gun shops. We had hunting guns: caliber 22 rifles and duck and dove hunting rifles. They were not harmless guns. We purchased a large number of automatic rifles, as well as cartridges that were not meant for ducks, but wild boars and deer. These weapons were not harmless. However, Batista felt so safe that all the gun shops were open for business during that period. They felt safe behind their military might.

Reporter: But weapons of war were not available, were they?

Fidel: No, they weren’t.

However, we were able to acquire some efficient guns legally. Some of our comrades would disguise themselves as hunters and bourgeois, and using their ID cards, they made their purchases at gun shops.

Our job was so efficient that the gun shops gave us credit. Hence, most of our last weapons were bought on credit.

Reporter: And did you hide these guns in a pit here?

Fidel: Most of the guns arrived here before Friday, on the eve of July 26. Most of the guns we had purchased were brought here by bus and train. Weapons of war as such, we had only three or four assault rifles only. For the most part, our guns were caliber 12 and 22 rifles, automatic rifles, only one machine-gun: an M-3 that was used for training at the university. Indeed, we used the campus extensively as training ground.

Reporter: I understand that at some point you had to stop using the campus…

Fidel: At that time, a lot of rivalry existed among youth organizations. Many students believed they were the hairs of the country’s revolutionary traditions. However, our movement had won over several university cadre members who helped make the campus available to train our people. In other words, our movement was popular; it wasn’t just university-based. However, we had people at the university, chiefly like Pedro Miret, currently a Politburo member, who was charged with our training activities at the campus. They were training everyone, and we managed to attract some of the campus employees, like Pedro Miret, and began using the campus to train our people who were of humble, rather than university background.

Reporter: So, you departed from here?

Fidel: Here we gathered both our guns and the participants in the attack of the Moncada Garrison. In the early morning of July 26, 135 men gathered here. Another group was in Bayamo. Our military strategy called for the takeover of Santiago and Bayamo in order to organize a frontline in the main direction of a possible counterattack by Batista.

Reporter: Comandante, wasn’t your strategy to seize the Moncada military barracks, arm the people and wage war?

Fidel: Our plan was to seize the guns existing at that garrison, and by relying on the existing discontent and hate of Batista, call a public general strike. We also intended to use the national radio stations to call this general strike. If our goal to paralyze the country failed, we would head for the mountains to wage an irregular warfare from there.

Reporter: Had you prepared a guerrilla warfare plan?

Fidel: I had. The plan had two options. Option one would try to cause a national uprising to overthrow Batista. If the national uprising failed or if Batista managed to react using superior forces to attack us here in Santiago de Cuba, or plan was to seize the guns from the barracks, head for the mountains and wage an irregular warfare from there. That’s exactly what we did three years later. The strategy designed for our takeover of the Moncada Garrison was the same that later led us to victory, only that this time we did not start at the garrison, but the Sierra Maestra mountain range (“the Sierra”). We waged war from the Sierra and eventually we defeated Batista using essentially the same strategy.

The Moncada strategy was, in general terms, the same we used later to oust Batista. However, the time (of the Moncada attack) was not right.

Now I am convinced that had we been successful and taken over the barracks and seized the weapons, and thereupon we had started a war against Batista, we would have defeated Batista earlier. Then again, we must consider the balance of powers in 1953.

If we had defeated Batista in 1953, imperialism would have crushed us. Between 1953 and 1959, a major shift in the global balance of powers occurred.

Reporter: The Cold War was in full upswing.

Fidel: And at that time, the Soviet state was relatively weak. We received critical assistance from the Soviet state, but in 1953, that assistance would not have been possible. That’s my opinion.

In other words, a success in 1953 might have been immediately foiled by imperialism. However, six years later, the time was right, because that shift in the global balance of power helped us survive. Had we been successful in 1953, we may have not survived.

Reporter: Events would have been more radical and…

Fidel: Since we succeeded in 1959, we had the opportunity to survive. That’s my assessment.

Reporter: An opportunity?

Fidel: Yes, an opportunity.

Reporter: It is significant that you say an opportunity, because it was quite narrow for…

Fidel: What would we have been able to do in 1953? We would have succeeded, we would have implemented the revolutionary platform we had designed, that platform would have invited an imperialist aggression, and we would have been crushed. If the Revolution had been successful in 1953, we would have been unable to survive. Such are the vagaries of history.

THE SURPRISE FACTOR

Reporter: Comandante, can we go back to talk about you?

Fidel: I will do as you indicate. Do you want me to show you the guns here? This is the only M-1 assault rifle we had, our only weapon of war.

Photo caption: Delivering a forceful speech as a student leader

Here is a sample of the guns we used. This is the only weapon of war we had, an M-1 rifle from the university. We used to train with this rifle at the campus. We had three of them. But this caliber 44 rifle was from the Buffalo Bill times. The bulk of our guns were caliber 12 and 16 rifles, and 22-mm rifles. We purchased all these rifles at gun shops. They were efficient pieces: automatic rifles. These too were automatic and loaded special cartridges we had bought. Even today I regard them as efficient guns.

Of course, we didn’t have any bazooka, antitank cannon or mortar. All of that would have been much better to have. But at that time, we only had these weapons for use to attack the Moncada Garrison.

Another fact: we had acquired army uniforms. The uniforms we were wearing were army issue. We obtained them through one of our comrades who was a member of the Batista’s army. Therefore, our 135 men were wearing military attires. The surprise element was the critical factor of our operation. We had these weapons and army uniforms.

We had planned to seize Cuba’s second largest military fortress from the Batista’s army. That fortress was being guarded by over 1 000 troops. We could have seized it. Even today, I think that our plan was not a bad one. It was a good plan.

Reporter: The problem was with that part of the force that detoured.

Fidel: Here is the main problem: We had planned to conduct our operation during carnivals so that our troop mobilization could be facilitated. In those days, the fortress beefed up its protection with Cossack patrols around the regiment. Our situation was definitively compounded when we clashed against this patrol that surrounded the barracks with presence on the streets we were driving on. Consequently, a shootout erupted outside the garrison. Otherwise, we would have been able to perfectly seize the garrison.

Reporter: can we take a picture from here?

Fidel: This is the pit were we hid our guns. One of the leaders of our movement, Abel Santamaria, who was in charge of the house, placed this jar on top of this tip. He filled the jar with dirt and planted a tree. Hence, our guns were kept under a tree planted here. That was the condition until July 26 when we removed the tree and the jar and extracted the weapons. (The interview goes on while Fidel drives the jeep on its way to the Moncada Garrison.)

Reporter: How many cars were you driving in total?

Fidel: The first to depart were the three cars that would take Hospital Civil. They were followed by the two cars that would take the Audiencia (“Courthouse”). And finally were the around 14 cars, including mine, which would seize the barracks. I had around 90 troops with me to take the garrison.

Reporter: In other words, the troops had been divided to capture different targets?

Fidel: Yes, 35 troops had been allocated to take Hospital Civil and the Courthouse in order to surround the garrison.

Reporter: Your brother Raul, Comandante, what was his mission?

Fidel: Raul was instructed to take Hospital Civil, sorry, the Santiago de Cuba Courthouse that overlooks the garrison. Abel was heading for Hospital Civil. Abel was the second in command in our movement. I dispatched our comrades with responsibility in our movement to different targets, so that in the event that I was killed at the barracks, the movement would not be left without a leader, understand? And Raul was sent to the Courthouse. We would take over the building around the barracks simultaneously with our attack on the garrison.

You can imagine the tension we felt as we were driving along this road, but we were quite determined. We harbored no doubt about our success. We had overcome the greatest difficulty up to that moment; i.e., organize and train our troops, acquire the weapons and prepare for the attack.

Reporter: Of course, you had dodged the repression.

Fidel: Certainly.

Reporter: This mountain right at the front, is it Gran Piedra where you headed to later?

Fidel: Later, we came back to the house in order to try to reorganize our forces, and a group of 10 or 12 men, including me, left for the mountains. While our guns were good to attack the barracks, they were not fit to fight from the mountains.

Reporter: Weren’t they large range?

Fidel: They were very short range.

Reporter: I figure that the scenery was rather different then. These pastures must not have been here at that time.

Fidel: All this is new. If you wish, you can reserve some of our material for our arrival there.

Reporter: We have material.

Fidel: It was along this bridge. Its only important feature is that it is a one-way road. When we were driving, another car was coming in the opposite direction. We had to wait for that car to cross, and then we drove on this way.

As you can see, the house was near the barracks. We turned here to enter the barracks.

Reporter: At the time of the attack, did you drive straight?

Fidel: Over here, we took this way. (Fidel and the reporters arrive at the Moncada Garrison where the interview continued.) Let me show you where the crisis erupted. The crisis happened here. Why? Because the Cossack patrol was coming in this direction and we met with it here. One of our cars passed ahead of us. That car had the mission to disarm the sentry. This car that was 100 meters ahead of us disarmed the sentry. However, the Cossack patrol saw our first car pass by and kept its eyes on it. When the Cossack patrol realized that the sentry had been disarmed, it became alert.

Photo caption: At Granjita Siboney estate, where the attackers of the Moncada Garrison gathered 25 years ago, Fidel answers questions of the reporters.

The Cossack patrol stood right here by my side. I pulled out my pistol to capture the patrol officer. At that time, the patrol officer realized that we were next to him and tried to shoot. I rammed my car against him. That happened around here. The officer moved away and I got out of my car. I made three movements: with this here, driving over here, and holding my pistol like this. When I stopped, the men who were coming in the cars behind mine concluded that they were already inside the barracks and got out to attack this point. I was forced to get out in order to remove our people from this building and to continue our attack. I spent between 5 and 6 minutes in that action. When I came back to my car, another car drove in reverse and hit mine. As a result, the fight first erupted outside the barracks, and our plan was to fight from inside.

Reporter: Then, the barracks was mobilized…

Fidel: The regiment mobilized and its defense was organized. That was our impediment. The Cossack patrol was a new feature that was introduced for the carnivals. I tell you this… I don’t know if can walk through here. At that time there were no trees here, as far as I recollect. The attack started there.

Reporter: That’s where it was supposed to start.

Fidel: It was supposed to start there when the patrol flanked us. When we clashed with the patrol, I had two intentions: first, to protect our forces that had seized the sentry, and second, take the guns carried by the Cossack patrol. If we had driven on and not paid attention to the Cossack patrol, we would have taken the barracks with our other cars.

Reporter: At that moment…

Fidel: Yes, we would have caught them by surprise. The Cossack patrol would have seen a car at the front and other cars behind it in line, and it would have not shot. I realize that today, but at that time, I tried to protect the forces that had seized the sentry and to take the guns held by the patrol officer. As result, the fight erupted outside the barracks, and since our people were not very much familiar with that facility, they began to attack in every direction. So I had to regroup our people for the fight. When we were going to enter the barracks, an accident occurred: one of our cars collided with mine.

Reporter: Your people were not actually familiar with Santiago de Cuba…

Fidel: Our people didn’t know. They were supposed to stop where I did. But when I saw that the Cossack patrol was going to shoot at our people inside the barracks, I tried to protect them by detaining the patrol officer. The Cossack patrol discovered us and tried to shoot. I rammed my car against the patrol officer, and that’s when the gun fight broke out. But the shootout first started outside the barracks.

Reporter: Was that the most serious incident?

Fidel: Indeed it was. Had that incident with the Cossack patrol not occurred, we would have taken the barracks, because the surprise factor was absolute. Our plan was a good one. If we were to design a plan now with our current experience, we would develop more or less the same plan. Our plan was good. In other words, an incident happened: an accident that foiled our entire plan. That’s a fact. Our failure to seize the barracks was attributable to our clash with the Cossack patrol that we should have ignored.

Reporter: Why did they call it Cossack patrol?

Fidel: It was called like this because it made rounds of the barracks. This specific patroller would come and go to the avenue. It was introduced for the carnivals. In other words, this patrol had not been anticipated. This Cossack patrol was apparently introduced during carnivals to prevent minor events. They had no suspicion that the barracks was going to be stormed. The patrol was set up for the carnivals held in Santiago. Before the carnivals there was no patrol. It was introduced during the carnival days.

Reporter: On the other hand, the carnivals were a favorable feature…

Fidel: They were helpful and facilitated our movement without arousing much suspicion. In other words, the carnivals favored us, but on the other hand, the carnivals were the reason why that additional patrol that was not there under normal circumstances was introduced, and it was that patrol that we clashed 80 meters from the barracks entrance. Otherwise, our men would have got out of their cars here and we would have definitely taken the barracks. In addition, we were wearing military uniforms. If the patrol had been caught, a defense line would have been drawn here. The problem was that they were able to mobilize the regiment. Otherwise, we would have caught the regiment in its sleep and we would have surrounded the barracks. We had taken the Courthouse and the other important buildings around the garrison. Then, we would have taken over this section and placed their forces against their backyard. Of course, carnage would have been inflicted, as was the case with the violent shootout that erupted when we clashed with the Cossack patrol. The way I see it, since our people didn’t have much shooting discipline yet, when they arrived here, they would have shot too, and carnage would have broken out. No doubt about it.

Reporter: At present, the barracks is home to a school. We see schoolchildren.

Fidel: Yes, it is a school. We removed the walls. Some are critical of this decision claiming that the place should have been preserved as historic site. But in the initial years of the Revolution, we didn’t have many schools and we were not thinking of history. Hence, we turned down the walls and established a school here.

Reporter: Yet, it is a historic site.

Fidel: All that is left is a small museum here. Someday it may be desirable to rebuild the walls to restore the site to its original shape.

WORKING FOR VICTORY

Reporter: Comandante, as I suggested, I would like you to address another point before we discuss general politics. An element that strikes anyone who has some knowledge of the Cuban history is the isolation that befell you after the defeat sustained at the Moncada Garrison and the resulting tragedy of so many comrades being killed: an obvious defeat, so my question is this, how come, in the midst of your isolation, you didn’t lose heart or abandon the struggle, but rather, you prepared your defense plea entitled “History will acquit me;” i.e., a political document that served as the basis for the continued struggle and the Revolution’s program?

Fidel: The reason is this: we were working for victory, not defeat, and we suffered a tough setback. But, this setback has cost the sacrifice of many comrades. If before the attack on the Moncada Garrison I felt obligated to my country, after the attack, that obligation grew stronger. In my view, given our intentions and purposes, I had no way but react the way I did, with more resolve and fighting spirit. No one knew how all that would end. We didn’t know if we were going to be murdered. But of course, we had to defend our ideas, our truth. Under those circumstances, the human being finds more incentives than under normal circumstances, and he draws strengths from these difficulties to address any problem. But the primary reason is that we were convinced that right was on our side. And that factor gave us strength to deal with those difficult moments, work hard, disclose the goals of our struggle to our people, confront the government’s slander campaign and lay down the conditions so that if our generation was unable to complete these tasks, the next generation would. In other words, a seed must be planted and an example must be set. It was not my personal example, but the example of those who had fought and sacrificed themselves. We had the duty to make our utmost effort to ensure that this sacrifice would not be in vain.

Reporter: In the midst of this predicament, did you find much inspiration in José Martí, Comandante?

Fidel: In fact, all the members of our generation were largely influenced by Martí and the historic traditions of our homeland. Those were traditions forged in the tough struggles for Cuba’s independence: highly heroic traditions that exercised much influence on us. At that time and even to this day, I was under a dual influence: the history and traditions of our homeland and Martí’s ideas, on the one hand, and the Marxist-Leninist education we had acquired during my years at the university.

These two combined influences: the influence of the Cuban progressive and revolutionary movements and José Martí ideas, and the influence the Marxist-Leninist conceptions were always present in all of us. One cannot separate these two influences in the context of the history of our country. In his time, Martí fulfilled the duties that were expected from him. And he represented the most revolutionary ideas of his period. For us, the combination between his patriotic and revolutionary thinking with the most modern revolutionary thinking and Marxism Leninism constituted our greatest influence and source of inspiration. It could not have been otherwise. In countries like Cuba, national liberation was closely related to social liberation.

Martí represented the doctrine of our people and society in the struggle for our national liberation. Marx, Engels and Lenin represented the revolutionary doctrine in the struggle for social liberation. In our homeland, national liberation and social revolution came together as the fighting banners of our generation.

Reporter: Comandante, let us move to another point. Comrade Alcaide told us a lot about the events in the Isle of Pines and discussed the ideological strengthening of the leadership group that was there. I have this question: Were you always confident that the political work carried out by your movement and another political force will lead to amnesty or did you consider a possible jailbreak to continue the struggle? Certainly, you didn’t intend to stay there for 15 years.

Fidel: No. I wasn’t planning to stay there for 15 years, but I clearly understood the political situation in our country. The hatred against Batista was widespread and Batista was a victim of his own contradictions. He was trying to legalize his regime and create conditions for an election that even if it was fraudulent, may at least serve as cover for his dictatorship.

We knew that given the existing public opinion, Cuba’s situation could not be resolved legally, unless the political prisoners were amnestied. We knew that an amnesty would be decreed sooner or later as a consequence of the public pressure and the contradictions of the regime.

Indeed, a jailbreak from the Isle of Pine was extremely difficult. We were under severe imprisonment in which surveillance was quite rigorous, and we were in an isle where a jailbreak plan was unlikely to be successful. This is why we relied on the political and mass movements that would exercise sufficient pressure on the regime to compel an amnesty of the political prisoners. In addition, we viewed that Batista felt strong and safe, and he underestimated the revolution and the revolutionaries, and at some point, as part of his political gambit, he would be obligated to promote an amnesty.

We were trying…First, we maintained a steadfast position of rebelliousness and decency while in prison. And of course, we encouraged a mass struggle for amnesty. By then, we were organizing our movement and developing plans for the future; that is, for the time the government was faced with the need to decree an amnesty. And that’s exactly what happened.

By the time we were released, we had a strategy for our struggle in place. In our opinion, the most important thing at that time was to show that a political solution was not possible; in other words, a peaceful solution to the Cuban problems with Batista in power was not possible. But we had to demonstrate that argument to the public opinion, so that if the country was forced to apply revolutionary violence, the revolutionaries were not to blame, but the regime. We claimed that we were ready to accept a peaceful solution of the problem in certain conditions that we knew will never occur. In a matter of weeks, the public opinion realized that no possibility existed for a peaceful solution of the Cuban problems with Batista in power.

We were always quite concerned, and given the influence of Martí’s traditions, we understood that war must be our last recourse. In our struggles for independence, Martí went out of his way to show that if war was to be resorted to, it was because no other option was available. This was present in the political traditions of our history. Just like him, we were trying to show that no peaceful solution could be realized with Batista. Once this claim has, in our opinion, been proven right, we embarked on the preparations for an armed struggle.

III. OFF TO THE SIERRA MAESTRA

PREPARATIONS FOR A HOMECOMING

We, the best known leaders traveled to Mexico. After the Moncada events we became quite familiar faces in Cuba. Our strategy was to prepare the movement internally and train some of our officers abroad in order to start the struggle simultaneously when those of us who were abroad would come back home. The primary task was to train officers militarily and gather a minimum required of weapons to resume the struggle. And Mexico was chosen because that nation had always maintained a tradition of solidarity and hospitality towards immigrants from different countries. However, we carried out our work in Mexico without any official support, either directly or indirectly. In other words, we operated in Mexico without any government assistance. While in Mexico, we carried out our duties in clandestinely.

We did face some legal issues. While our activities were not targeting the Mexican state, actions such as gathering weapons and training personnel were in violation of the Mexican laws. That led to some issues and we found ourselves in some difficult spots: some of us were arrested, but at that time, we were helped by the fact that general Lazaro Cárdenas, Mexico’s most prestigious and internationalist character in recent times, became interested in our situation. Lazaro Cardenas commanded great prestige in Mexico, and the fact that he expressed interest in us helped solve our legal status, and to a certain extent, mitigated the repression we were under in Mexico at that time. As a result, we gained time and completed our preparations before we came back to Cuba.

Photo caption: In jail after the bold action of July 26, 1953

Batista was quite active too. He was keeping paid agents in Mexico and they were Cuban agents. He was trying to exercise influence on each Mexican state to crack down on our activities there.

We left Mexico by late November 1956 in absolute secrecy. At that time, we were being persecuted by the local authorities as a consequence of the allegations made by the Batista government.

I am not criticizing the Mexican authorities. Under those circumstances, they had the right to enforce on any breach of the Mexican laws. In to a certain extent, we found ourselves forced to break the Mexican laws in order to realize our patriotic purpose in Cuba.

That contradiction occurred. Difficulties ensued. Some of our weapons were confiscated and we were forced to leave Mexico at a time when the local authorities were looking to arrest us and of course prevent our revolutionary activity. The last few days of our stay in Mexico were characterized by serious challenges. Notwithstanding, and in part thanks to our experience in underground struggle, we managed to overcome these difficulties and sail out from the port of Tuxpan, if my memory doesn’t deceive me, on November 24, 1956. By the way, the weather conditions were awful and sailing had been banned for those days. But we had to brave the weather anyway.

The fact that we had managed to sail out represented a big step forward. Three or four days later, Batista learned about our departure from Mexico. Instructions were given to the Navy and Air Force to spot our small vessel, a 60-odd foot long yacht that was carrying 82 men.

We sailed in bad weather conditions far from the southern coast of Cuba and landed off the province of Oriente. Fortunately, we managed to arrive before the Navy or the Air Force discovered us. On the night of our last sailing day, we were far from the shoreline, and we sailed between 80 and 100 miles to arrive at the Cuban coasts on December 2, 1956.

Reporter: Comandante, we understand that one of your commanders or the ship master was a Batista navy officer who had joined your struggle.

Fidel: Not really. He was not a former officer of the Batista navy. He was a former officer of the constitutional navy, which is a different story. He helped us by steering our yacht. Also with us was a captain from the Dominican Republic (“DR”), a revolutionary who had seamanship experience. Later on, he joined Caamaño for the DR revolution and was murdered. He was coming with us too. Also with us was a former navy lieutenant. However, all of us combined had poor knowledge of the Cuban coasts. Our information was scant. As a result, some difficulties aroused. Notwithstanding, we sailed 1 500 miles to land in Cuba. By the time we landed, we had two inches of fuel left in our tank. In other words, we had fuel for just a few more minutes.

Reporter: That is to say, you were always on the brink of peril.

Fidel: I think that comes with the territory of any revolutionary.

WILL TO RESIST

Fidel: We landed around here 20 years ago.

Reporter: The seabed is visible.

Fidel: We are approaching the site where we landed(4). You will see it now. It is right here, look. This is where we landed. You can film it now. It is right here. Film now, otherwise we will pass the site. In fact, we reached the ground one kilometer to the south from here. As can be seen, we landed on a flat area.

Reporter: Was there a miscalculation of the landing spot?

Fidel: It was about dawn, but before sunrise, one of our men fell in the ocean and we spent around 30 minutes to find him and bring him back on board. It was dawn. The ship master was not quite sure of where we were. He had been spinning around. I asked him, “are you sure this is Cuban mainland?” He answered, “Yes.” I said, “Set the course in this direction toward the beach at full speed.” And we arrived at the beach. However, our landing site was a huge swamp that covered several kilometers. We spent around two and a half hours crossing the swamp. It was very difficult. We were sinking to our waists. Finally, we reached firm ground, but the place was not good.

We had two inches of fuel in our tank when we landed. It would have been better to land a bit further to the east, but we didn’t have enough fuel.

Reporter: Therefore, you were far from the Sierra, weren’t you?

Fidel: We were. The fuel was not enough and the site was flat. Had we landed 50 or 60 kilometers toward the east, the war would have ended earlier.

Fidel: Do you mean closer to the Sierra?

Fidel: Yes. If we had landed near the mountains...We landed at a flatland and our enemy managed to lay a siege around us. The situation was very difficult. Had we landed near the mountains, the war would have lasted much shorter.

Fidel: The… would not have occurred.

Fidel: It would have lasted maybe 12 or 15 months. The war lasted 25 months. On day 3 after our landing, we suffered a serious setback. The enemy attacked us by surprise, and our forces scattered. We sustained many casualties, and just a few of us managed to survive this situation.

Reporter: That was at Alegria de Pio.

Fidel: Yes, it was Alegria de Pio. Later, we managed to gather a few men with a few rifles, but as you can see, the mountains are far from our landing site; the first hills are around 40 or 50 km away. It’s over here where the Sierra Maestra begins to rise.

Reporter: Comandante, at this juncture, after Alegria de Pio, was the assistance from the peasants who eventually joined you critical?

Fidel: It was. Initially, we were under siege for many days. I had a rifle, and I had two other men with me. One had a rifle, but the other man didn’t. At that moment, I had a rifle and 100 rounds of ammunition. Another comrade had a rifle and some 40 rounds. Eventually, Raul with four other men joined us. They had four rifles with them, plus a fifth rifle from another man who had failed to move on. In total, we had seven rifles.

Reporter: Was that the small group that managed to escape Alegria de Pio?

Fidel: We were all scattered.

Reporter: Those who were with you, were they…?

Fidel: They were two. One carried a rifle. The other didn’t.

Reporter: Was Almeida in the other group?

Fidel: Almeida was in a third group, with Che, Camilo and other comrades. Initially, we gathered a group with seven rifles. This new highway you see here didn’t exist then as such. It was a dirt road. It was around here that the army laid its siege. Along this highway that was a dirt road then. Later, we took to the task of collecting some guns. When we arrived at this area, we began to make contact with the peasants. They helped us cross the highway or dirt road and make it to the mountains of Sierra Maestra.

Reporter: Were the peasants Guillermo Garcia and…?

Fidel: Guillermo was the first peasant who made contact with us. He was from this area and was a member of our movement. He had heard of our landing. He was following the news.

Photo caption: In the US, like in Mexico, during the intense activities in preparation for the homecoming and final liberation

One early morning, we crossed the dirt road and walked about 20 or 30 kilometers.

Reporter: Everything Celia had prepared was in Niquero, wasn’t it?

Fidel: In the Pilon area. In fact, the best landing site was more to the east. We landed here because daylight had broken out and because we were not very much familiar with the terrain or the coast.

We had developed a plan to take a small fort located near here and then move on to the Sierra. But given the way our landing had occurred, that operation was absolutely impossible. We had landed at a swamp and the enemy had time to mobilize and prepare military operations against us. In fact, the enemy scored a victory, because it managed to disperse our 82-strong expeditionary group.

Reporter: How many of you were left?

Fidel: Eventually, we were able to gather fewer than 20 of us with seven rifles. Some of our troops were unarmed. Later, we were able to pick up some of the weapons that had been scattered. Our first successful action against the enemy occurred on February 5. By then, we had 16 guns.

Reporter: Was it at El Uvero?

Fidel: It was at La Plata. We attacked that position in the early hours of the morning. If my recollection is right, it was around 2:40 a.m. We fought them for more than one hour. We took a small fort and seized 10 weapons. Our group grew to around 30 men. By then, our growth was based on mountain peasants who were joining us.

Reporter: Comandante, after your defeat at Alegria de Pio, how did you manage to regroup your forces, break the seizure and keep on the fight, without letting go your faith in victory?

Fidel: The way I see it…No one know who or how many were alive. For my part, I intended to move on with the struggle, even if we only had two rifles. I had no news about the rest of our people. For his part, Raul had also intended to keep the struggle on, and then we met. When Raul and I met, we had seven rifles. We recovered additional 6 or 8 rifles that had been lost or scattered. Our first action involved between 17 and 18 men. By that time, we had 14 rifles and some pistols. Our first military action was carried out by a very small group. But we had the experience of the Moncada events and we were determined to keep up the struggle. We were convinced that our idea was right, even if we had sustained a very serious setback. This is Sierra Maestra…the aircraft could not strike…We were under siege by the army for 18 months. We were surrounded by sea and ground.

In this initial period, our primary objective was to survive. And our ability to survive depended heavily on our own selves; that is, the small group stationed in the mountains. In fact, at that time, all we had was an idea, an organization in the cities and our will to resist.

Under those circumstances, what the guerrillas would do was very important. The guerrillas could be exterminated at any time. We were close to being exterminated due to an act of treason by a peasant. In other words, a peasant who had been entrusted with a mission was captured by the army. He was offered pardon for his life and many other things. Hence, he betrayed us. Our first guide, one of our guides, betrayed us. The primary psychological factor involved was that, in his eyes, our forces were small, and the army was very big. And he lost faith in our possibility to succeed. Hence, he placed himself at the service of the army. That peasant’s action in coordination with the army put our forces on the brink or annihilation. Those were tough days, because he was our leading guide: the man who was our eyes and ears was betraying us and giving away our position so that the army could surround and liquidate us. And they were close to success. But we figured them out.

Reporter: You figured it out on time.

Fidel: Well, not on time. We figured it out particularly after the army’s latest action that nearly exterminated us. We realized he was betraying us. I realized it. Other comrades were skeptical and could not believe it. I presented to them the reasons why I believed he was betraying us. And the events proved me right. But we would have been exterminated, but for a matter of minutes.

Reporter: Were you surrounded?

Fidel: Yes, we did. We were being surrounded, but I began to suspect and we started to move. And we met up with the army on the fringes of its seizure. That peasant was coming with the army acting as its guide at a time when was supposed to be on a mission given by us. We saw him, but we already knew he was betraying us. He had led us to a site where the army could surround us. We were spared by the fact that it had rained heavily the day before and they (the army) deferred their planned action for the next day. But on the following day, we figured it out on time because we captured a prisoner. While our forces had been instructed to remain unseen, one of our sentries captured a man. I asked him a number of questions, and by the movements made by the army the day before, I realized that they were surrounding us. At that moment, I concluded that we were being betrayed, and instructed that we moved away from that spot immediately. We set up positions on the high hills, where the army was completing its seizure. We were pretty close to extermination. The comrade who was next to me was killed.

Reporter: Was that the second time?

Fidel: That happened at a place called Altos de Espinosa. That was the occasion when we were the nearest to entire annihilation. But we managed to survive and escape that seizure. And we learned our lesson too.

Photo caption: With Raul, Almeida, Ramiro Valdes and Ciro Redondo during the years of war at the eastern Cuba mountains

Our organization was quite small in that region, but we received assistance right from the initial moments: We were helped by Guillermo García, we were helped by Ceila who was in Manzanillo and sent us our initial supplies, clothing and money. We were paying the peasants for everything they gave us. At the beginning, the peasants were quite scared because of the army repression, but the Revolution gradually won the peasants over. In other words, there was no previous work done with the peasants. The work was carried out during our struggle. The army was repressing and committing lots of crimes, and it was sowing terror. For our part, we respected the peasants and we paid our way to them. Little by little, the peasants joined our ranks. And eventually, all the peasants were on our side.

THE CORE SITE OF OUR OPERATIONS

Fidel: The name of this site where we are now is La Plata. We scored our first win against the Batista forces here. It occurred about one and a half month after we had landed and several weeks after they had managed to disperse our entire forces. We were able to assemble around 17 men on this spot. During those days, acting on the belief that our guerrilla forces had been liquidated, a patrol of Batista marines and soldiers was busy evicting peasants and committing all sorts of abuses and misdeeds in the interest of a local big landowner.

Reporter: Comandante, you will excuse me, their belief that your forces had been liquidated must have given you some respite…

Fidel: It gave us some advantage, because they became careless. They were moving on and holding peasants as prisoners just like the peasant who spoke with you. The peasants were being tortured or murdered as part of their effort to sow terror among the peasantry. We closed in on them by the west, and from these heights, we monitored the movements and location of their patrol.

When night fell, we came in closer and captured the army patrol’s guide who was an employee of that landowner and was feeding information about the peasants who were standing up against the evictions. They were cracking down on those peasants. The captured guide gave us full details of the patrol’s facility. And in the early morning, we attacked them. We were 17 and they were around 12 stationed in two small barracks. After around one hour of combat, they surrendered. But by the time they surrendered, most of them were dead or injured. They were the first prisoners we made, but of course, we could not take them with us. We gave them our medicines. We always pursued the same policy toward our enemy: we respected their lives, and naturally, their injured. We consistently applied this policy on our prisoners during the entire war. We took their guns and increased our ranks to some 30 men.

By sunrise, we moved toward the other river bank where we had been before, in the direction of Palma Mocha. The enemy reacted with anger and sent a large number of troops, hundreds of soldiers. But they sent ahead a group of paratroopers that we ambushed causing them defeat with many casualties. We also seized some guns from them. These two actions took place on January 17 and 22, 1957. These were our first military victories against them.

This site has historic significance. North from here, along the river course, is La Plata, the core site of our operations. For many months, our war was waged within an area that was 30 km long and 20 km wide; around 60-sq kilometers. Their forces, as well as ours, moved within this area that was the theater of our actions. Of course, we were weak initially, and their columns could travel across the mountains uneventfully. As time went by, we learned their ways and began to ambush their columns, but we could not prevent their penetration. We would inflict casualties and seize some of their guns, but still, they would penetrate.

Our forces were growing, and by the summer of 1958, we were around 300 men. For their last offensive on the Sierra Maestra, they gathered 10 thousand troops, and we were 300. However, our 300 troops were already highly experienced. We had relatively little ammunition, but in the face of this offensive, we held our positions. We set up our positions o the different access points to the Sierra. We held on and delayed their advance, while we were inflicting casualties on them.

The battle of their offensive and our counteroffensive lasted 70 days. Combats were waged virtually every day during those 70 days. The critical event that marked the defeat of their offensive was the battle of El Jigue that was fought around 5 km from here. We managed to surround a battalion that was being led by a very smart commander. We had been hunting that battalion, and they had applied daring maneuvers, and managed to escape. Eventually, we surrounded them with 30 of our troops. The rest of us, the bulk of our troops; i.e., some 90 men, were deployed in the direction of the beach, where another enemy force was stationed. Using 120 men, we waged this 10-day combat.

It was quite a special situation. At that time, we had surrounded only one enemy column; while we were being surrounded by several enemy columns. They were trying to erode our defense, while we were trying to cause the seized battalion to surrender. We managed to destroy their reinforcements that were coming from this direction, from the beach. Their primary reinforcements were coming from the beach line, and that’s where we had deployed the bulk of our forces. As we seized more guns in combat, we increased the numbers of our ranks. Eventually, we liquidated their reinforcements and their battalion surrendered. As a result, we obtained a lot of weapons and ammunition, and that event represented a turning point in their offensive. From then on, we went on the offensive and dislodged them from the Sierra Maestra.

By the end of this offensive, we seized over 500 guns and inflicted over 1 000 casualties, including 400 prisoners that were turned over to the Red Cross with the involvement of the International Red Cross. Those prisoners were released as part of our prisoner policy.

By then, we were 800 strong, and with this force, we launched an invasion of our entire country, except for Segundo Frente, where Raul was stationed. When the enemy embarked on its offensive, we brought in Almeida’s forces that were near Santiago, Camilo’s forces that were in the plains, and Ramiro’s forces that were in the east. We gathered all these troops, and this is why we managed to count on 300 men. The only troops that we didn’t mobilize, because they were too distant, were those led by Raul at Segundo Frente.

After that enemy offensive, by the second half of 1958, we dispatched columns to Santiago de Cuba, the north of the province of Oriente and the province of Camaguey, plus two other columns, one led by Che and the other by Camilo, that were sent to central Cuba. This is why that battle meant a turning point in the war.

The army outnumbered us. Batista had between 70 000 and 80 000 men under arms. By the end of the war, we had 3 000 men under arms. However, we were keeping 14 000 soldiers under siege in Oriente. While they had a lot of men under arms, they had to protect cities, facilities, bridges and communications. The largest force they were able to put together to fight was 10 000 strong. That was the occasion of the battle I have just described.

Reporter: Is it here where the actions involving that commander took place?

Fidel: Yes, it is. Commander Quevedo was heading their battalion. He was a smart chief. He fought hard and held on for 10 days. They had run out of food and water and sustained many casualties. He was a decent officer with no history of crimes or abuses against the people. He became our prisoner. We kept as prisoners only the most senior commanding officers. Later, he joined our ranks and helped us.

Reporter: Where is he now?

Photo caption: During the days at Sierra Maestra

Fidel: He is currently our military attaché in Moscow. He wrote a book about that battle. He was a capable commander; indeed, a capable enemy.

Reporter: And at the end of that battle, did you let him keep his pistol?

Fidel: At the end of that battle, we let all their officers keep their pistols, not just him. But listen to this story: I was growing impatient…This is the story: On the last day, we were negotiating their surrender, and the commander of the besieged troops advised us that if by 6:00 p.m. their reinforcements had not arrived, they would surrender. They had no hope of success, because we had defeated their reinforcements. We were using loudspeakers...and forwarding the letters we had occupied from their reinforcements. We were keeping them informed. We had the member soldiers of their reinforcements speak on the radio too.

However, I was so impatient to see the materiel that we would seize that when the surrender was being negotiated by nightfall, I decided to enter their camp incognito, as if I was one of the members of our negotiating team.

Reporter: Enter the enemy camp?

Fidel: Yes, the enemy camp.

Reporter: Wasn’t that a major risk?

Fidel: Well, it is relative. By then, they were demoralized. I was not planning to identify myself; rather, I was acting as one of our negotiators. Hence, I entered their camp when their soldiers were still armed. After I was there for a few minutes, all of them recognized me and their behavior was impeccable. They treated me with utmost respect. That’s what happened. I entered their camp while they were still armed. Of course, mine was a reckless move or a miscalculation.

Reporter: But you did fine.

Fidel: Yes, it came out well. They were already engaged in talks with our forces. Our troops were supplying water and cigarettes to them from our trenches to theirs. The last day had witnessed what can be regarded as a fraternal atmosphere. There was no violence. No fight had erupted in several hours. However, Quevedo was there. Quevedo was respected commander among his troops. He was quite respected. What’s more, he was a gentleman. Of course, all those factors exercise influence. Possibly, my overall review of the existing situation gave me confidence to do as I did, but the events didn’t turn out as I had planned. I really thought I could come in unidentified. But for some reason, they immediately realized who I was, in spite of the fact that it was nighttime.

A NEW ARMY IS BORN

Reporter: Comandante, after the Revolution took power, its victory didn’t solve all the problems; instead, major challenges emerged, such as the confrontation with that first government, the need to enhance the revolutionary power, and quite soon, the imperialist onslaught and the blockade. One key factor noticed by any outsider is the dismantling of the tyranny’s army that was the armed wing of the bourgeoisie, an obviously dangerous factor. We can’t clearly understand how come that army was demobilized so quickly before it could regroup and gain strength and efficiency.

Fidel: Actually, we defeated Batista’s army. We virtually liquidated its elite forces at the Sierra Maestra. While it troops were numerous, its elite force had been defeated. When an army sees its operating troops liquidated, that means real defeat. Add to that, the existing total public support. Therefore, they couldn’t do much militarily.

In the final days, we were holding 14 thousand soldiers under siege in Oriente, and our island had been split in two parts. Initiative was on our side and the Batista’s armed forces were demoralized.

Under those circumstances, they tried to make contact with us. At a meeting with me requested by their operations commanding officer, he recognized that they had lost the war and asked us what they should do. I said that the army had fallen in much discredit; however, in my opinion, its ranks included good and capable people who had unfortunately been faced with a situation in which they had to either defend their institution or defend the regime alongside their institution. He accepted our proposal that they staged an uprising.

Photo caption: A new revolutionary and people’s army was born out of the history victory

We invited the defeated army to issue a statement and join our revolutionary force. We also said we were absolutely against a coup d’état. I even recommended to their operations commanding officer to stay away from Havana, organize an uprising with his troops in Oriente and join us. He agreed, but failed to deliver. Instead, he traveled to the capital city.

We had set three conditions; i.e., first: we will not accept a coup d’état. Second: we were opposed to any attempt to save Batista. And third: we were against any arrangements with the US embassy. Those were our three conditions that they accepted. However, they did exactly the opposite. They went to Havana, organized a coup, made arrangements with the US embassy, and helped Batista flee.

This is why when a coup was staged on January 19th, we used the radio and instructed our troops to reject any ceasefire and keep up our offensive at every front. And we called on the workers and people in general to go on a revolutionary general strike.

Our forces and movement were highly influential, and the regime was crumbling. Let me give you an example: all the radio and TV stations tuned in to our Radio Rebelde. The radio and TV employees synchronized their stations with Radio Rebelde. And the entire people, the workers in particular, went on an absolute strike. Our forces and columns didn’t observe any ceasefire; instead, they moved on with our offensive, and within 72 hours, we had virtually disarmed the entire army.

In the early days of December, the people took hold of all the weapons. Tens of thousands of Cubans seized weapons and the army was virtually dissolved.

Had our conditions been accepted, we could have saved many officers for the Revolution; that is, career military officers who had no history of crime, murder or torture. It was just a group of military officers who lent themselves fully to the crimes committed by Batista. They were a clique. However, within the armed forces, there were career officers who had no direct responsibility for those crimes.

If they had accepted our proposals, a new army would have been born anyway, as an indispensable requirement of the Revolution. However, we would have been able to rely on the cooperation from a larger number of officers. In any case

, we did receive cooperation from a number of officers. Some military officers had been incarcerated on charges of conspiracy against Batista, and many of those officers joined us after the triumph of the Revolution.

Some officers who had fought against us were gentlemen and decent, and eventually they joined us. Consequently, a number of officers from the old army did cooperate with us, but many could not be saved, because the army’s demoralization and disintegration were absolute. Furthermore, the conditions were not the best to rely on the cooperation from many of these officers.

In fact, a new army was born. In my opinion, the Revolution was made possible thanks to the replacement of the old army by a new revolutionary and people’s army, a new army that currently has much more technical training: ten times more technical training than the Batista’s army ever had. At present, we have ten times more officers who are, by far, better trained than the military our country ever had. Ours is a revolutionary army with regular troops, as well as reservists who are mostly trained workers and peasants. It is a people’s army which strength stems not so much from its professionalism or technology, but its identification with the people’s interests and its huge reserve of workers and peasants that constitute a mass of combatants in case of war.

December 2, 1977